Why Invisibility Isn’t a Superpower

For so many years I believed that maxim that women are not born but made. Maybe that’s part of why I love the virtual so much — I’m not expected to believe that idea. When I was trying to live as a woman, every act of gender performance was a simulation. I became expert at constructing just the right textures on my face, just the right vectors on my chest, just the right animation as I walked in high heels.

Everyone around me took this simulation as reality. They looked at an avatar and saw a person. Why would they do that if their femininity was constructed too? Maybe I was the only one who was a simulation. You don’t become a woman through daily rituals of self-construction. Women are not products of skilled craftsmanship.

Eventually I had to come to terms with who I am.

My mother is having trouble accepting me. She tells me that by coming out as trans, I’m forcing other people to change the way they think of gender in order to accommodate me. I’m attacking a stabilising structure in their world, and in doing so I’m personally attacking my family. But her fearful perception of how the world responds to people who challenge its boundaries is completely at odds with my experience of independent adult life.

In the games industry, I don’t feel like an unwelcome imposition on the world. The work done by trans people making games, and the positive critical attention certain key titles have received, have been a source of much-needed comfort and affirmation. Trans experiences are no longer silent. I get to feel like perhaps this industry is safe for me as I slowly come out to more people.

Lim was extraordinary for me. The very idea that someone had made a game about ‘multivocal bodies’ made me happy, and to find that it represented my fears of social coercion so elegantly was a delight to me. I felt elated just to sense that a fear of mine was shared by someone else.

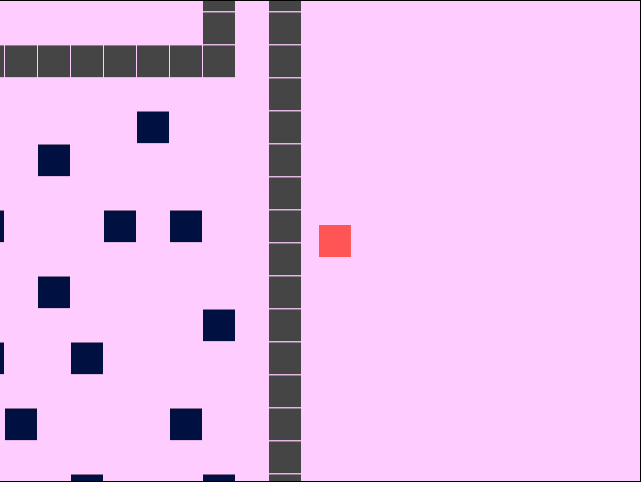

There is a collision glitch in Lim that pushes the main character out beyond the walls of the labyrinth. After I was pushed out, there was nobody left to fight with. Nobody left to blend with. I found my way to the end of the path, where another flashing square was waiting for me, on the other side of a wall. I pressed against the wall, mashing the keyboard to push left, push left, and find solidarity with the other square. It stayed still in the middle of its little room, as if it neither knew nor cared that I was there.

I worry about being shut out. Even as I feel affirmed by the games being made by trans women, I also feel uneasy reading my own experiences into them. Sometimes I attribute that to a lack of transmasculine voices. When Brendan Keogh wrote for Polygon about ‘queer games’ and their developers, what he meant specifically was people whose experiences might be well described by Liz Ryerson’s quote in that piece:

“A lot of trans women grow up with games being socially acceptable, because they’re raised as male. Then when they transition, they have to confront the fact that they are not part of this ‘gamer’ culture anymore. There’s no space for them there, so now we have to create that space.”

The implication is that the queer games space is a women’s space. I have always felt guilty in women’s spaces. Even before I understood myself as transgender, I always felt like I shouldn’t be there, that my presence was ruining things. So it’s hard for me to tell if I’m not part of that space Ryerson refers to, or if I am just too uncomfortable venturing there.

If mainstream culture mostly embraces me, and I still feel worried about being stuck outside of supportive spaces, is it because I don’t really belong in them?

When I first played Mainichi, I felt jealous. The chibi image of its designer, Mattie Brice (Editor in Chief of re/Action) spends time on her appearance because it makes the world see her for who she is. I know this, but I don’t want to make her to do it. When I was trying to live with the femaleness I was assigned at birth, the daily craft of making myself appear normatively female left me unable to identify with my own reflection. I can’t imagine the feeling of affirmation that Mattie gets from makeup. I’ve never had it.

When I first played Mainichi, I felt jealous. The chibi image of its designer, Mattie Brice (Editor in Chief of re/Action) spends time on her appearance because it makes the world see her for who she is. I know this, but I don’t want to make her to do it. When I was trying to live with the femaleness I was assigned at birth, the daily craft of making myself appear normatively female left me unable to identify with my own reflection. I can’t imagine the feeling of affirmation that Mattie gets from makeup. I’ve never had it.

Since I gave up the craft of pretending, I stopped being targeted by creepy men on the street. I feel guilty, like I’ve simply opted out of something that women have no choice but to endure. I didn’t choose transmasculinity in pursuit of privilege, but I know that my discomfort being read as female is partly my own dysphoria, and partly other people’s misogyny. Mattie doesn’t get to choose whether or not that guy on the street harasses her. Did I get the choice she didn’t?

Mattie also gets choices that I don’t have. Nothing I do with my face in the mirror in the morning will convince attractive baristas to read me as male. Inaction doesn’t cause my gender to default to male; it makes me illegible, invisible. It might be that invisibility that makes my experience different to what’s represented in the games that have brought me so much hope.

In one part of Dys4ia there is one pixel shape and one brick wall that the shape will not fit into. In my memory, the shape is a tetris piece, and the wall is made of other tetris pieces; they are just like me, except that they fit and I do not. But when I go back to replay the game, I find the wall is actually made of bricks. What Dys4ia’s creator Anna Anthropy depicts as structural, I experience and remember as personal.

In one part of Dys4ia there is one pixel shape and one brick wall that the shape will not fit into. In my memory, the shape is a tetris piece, and the wall is made of other tetris pieces; they are just like me, except that they fit and I do not. But when I go back to replay the game, I find the wall is actually made of bricks. What Dys4ia’s creator Anna Anthropy depicts as structural, I experience and remember as personal.

My false memory of Dys4ia might be the voice of my mother playing that game for me. To her, the wall is made of other tetris pieces, and I risk breaking them apart. But I have a choice. I can still just slip through that space they set aside for me. Even in men’s clothing, my gender remains invisible. If I just do nothing, if I stay silent and stay invisible, nobody needs to get hurt.

Anna changes from a rigid, ill-fitting tetris piece to a vibrant, fluid, shifting entity. But only after starting HRT. Is my fluidity caused by my estrogen levels? Or is it mine? Would testosterone make me inflexible? Would it make me aggressive? Can I become visible without attacking the other tetris pieces?

Maybe none of this is about the physical. Maybe the physical is just a container for other issues.

Maybe none of this is about chromosomes, and maybe hormones won’t change anything. Mattie gets harassed because of who she is, not because of the choices she made in the bathroom that morning. Unable to balance Mattie’s physical and emotional needs with her social needs, I found myself longing for the simple solution presented in Dys4ia. Surely if you get on hormones things will change? Maybe I want the physical to contain this. After all, we can change the physical.

In one level of Dys4ia, Anna attacks the wall itself, breaking it apart. In a subsequent level, the wall is exactly as it was before. Maybe we can’t change anything.

I don’t have that experience of growing up with games being socially acceptable for me, and then losing that feeling of inclusion as an adult. At the same time, I don’t yet know if I am now part of mainstream ‘gamer’ culture simply by virtue of having informed people that I’m a man. One advocacy group that aims at ‘exploring transgender issues in gaming’ calls itself ‘press xy’, a clever pun mockingly referring to chromosomes that are not mine. In a discursive landscape where ‘queer games’ are made by women, I feel invisible.

Invisibility might be a male privilege. Invisibility is safety. Invisibility is such a valuable privilege that it’s hard-earned in many mainstream video games; an advanced technology or magic technique that allows you to move untroubled through the worlds of Skyrim, Metal Gear, and others. Invisibility often serves a power fantasy.

Invisibility as a power is about the ability to pass through the world without consequence. In games with a stealth element, to evade the gaze of other human beings is to evade reprisal for being where you do not belong. The fantasy violence of these games might be a dramatic stand-in for less overt social violence that controls our behaviour by letting us know that we are being watched. To be invisible is to be exempt from that control.

But invisibility doesn’t actually make me feel all that powerful.

3 Comments

My own daughter is a trans woman. She came out to her mother and I at roughly age 19.

Because of her, I’ve attended conferences and such, and had the privilege of meeting many other trans women and men. What I discovered is that they inspired me. There is a basic human process involved. Every single human being is faced with the problem of expressing their inner truth to the world, but trans people have a fairly extreme version of this, and so many of them face down that challenge and work to overcome it with style and grace.

Your mother is accurate when she says you are forcing people to change the way they think about gender. This happened to me, and it was a good thing.

Pingback: New Games Online » This Week in Video Game Criticism: From Animal Crossing to Modern Warfare

Pingback: Fully Human: What Gamers and Developers Can Learn from the Victory over DOMA