Shattered Memories

Silent Hill and the fear of God are combined by Jake Spencer in this tale of judgment of every action one takes… and doesn’t take.

“I’m going to go over there.” My friend Bobby was pointing toward his mom. “Just for a second.” The two of us had been climbing through the play structure at Little Caesars Fun House, Detroit’s short-lived answer to Chuck E. Cheese at the dawn of the nineties. We couldn’t have been more than three years old.

“I’m leaving you alone, but you’re not really alone,” he said in the most comforting tone his toddler voice could muster, “because God is here with you.”

Dr. Sobel digs into a bucket of ice with a pair of tongs and tosses a few cubes in a glass tumbler. A distant look crosses his face as he pries the lid off a tall bottle from his well-stocked bar. He pours a finger, then ambles over to flick on a floor lamp. The extra light only draws attention to the darkness enveloping the musty office. He takes a hard sip of his drink and waits for his new patient to arrive.

Dr. Sobel digs into a bucket of ice with a pair of tongs and tosses a few cubes in a glass tumbler. A distant look crosses his face as he pries the lid off a tall bottle from his well-stocked bar. He pours a finger, then ambles over to flick on a floor lamp. The extra light only draws attention to the darkness enveloping the musty office. He takes a hard sip of his drink and waits for his new patient to arrive.

Dr. Sobel is not a comforting man.

Our session begins with a simple questionnaire. “Try to answer truthfully,” says Dr. Sobel, arching an eyebrow at me. He smiles. “It’s easier that way.” It’s clear my therapist doesn’t trust me any more than I trust him.

I make friends easily. True or False?

Having a drink helps me to relax. True or False?

I have enjoyed role-play during sex. True or False?

These questions are getting more personal than I expect from a video game. The virtual doctor snatches the form away from me as I reach the end. He turns away to review my answers, then glances back at me.

“Never cheated on a partner. Really?”

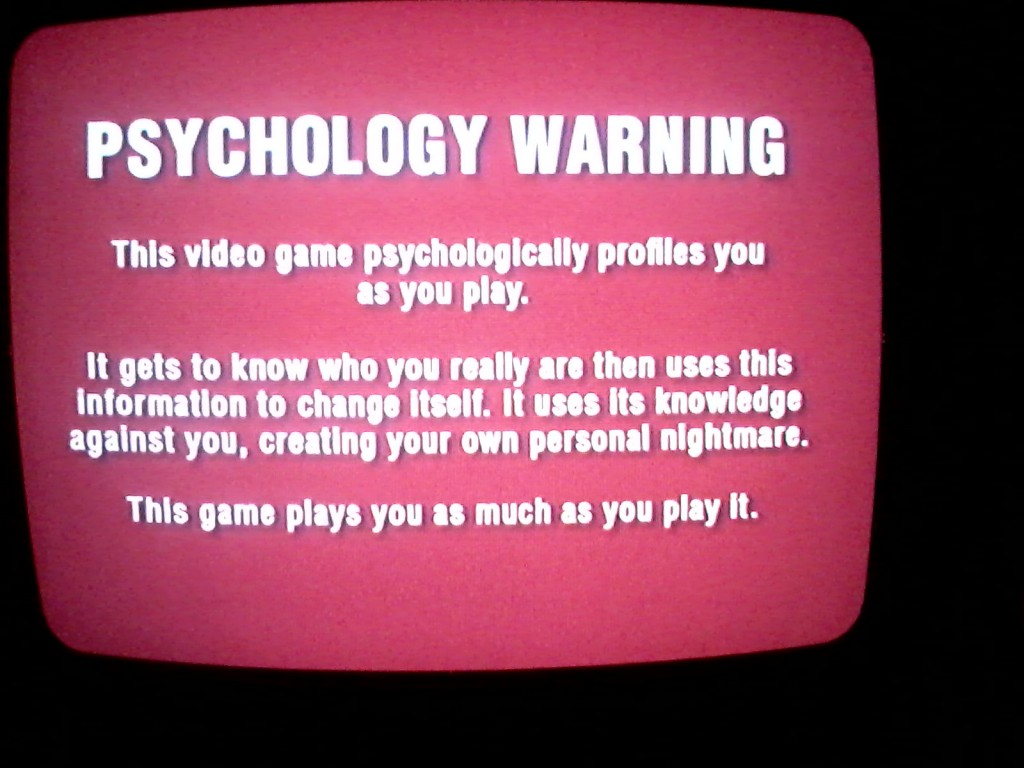

These are the first playable moments of the 2009 horror game Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, and they establish a tone by putting a face on the game’s most notable system, the psychological profile. Now, keep in mind that this was released two yeas after BioShock’s binary take on morality and Mass Effect’s Choose-Your-Own-Adventure branching paths had brought hard decisions (and consequences) to the Halo crowd. Player choice systems, certainly among the defining tropes of this generation’s video games, were well worn and mainstream even before Shattered Memories had entered production, but no mainstream release had approached the concept like this. In that space, it’s sill unmatched.

These are the first playable moments of the 2009 horror game Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, and they establish a tone by putting a face on the game’s most notable system, the psychological profile. Now, keep in mind that this was released two yeas after BioShock’s binary take on morality and Mass Effect’s Choose-Your-Own-Adventure branching paths had brought hard decisions (and consequences) to the Halo crowd. Player choice systems, certainly among the defining tropes of this generation’s video games, were well worn and mainstream even before Shattered Memories had entered production, but no mainstream release had approached the concept like this. In that space, it’s sill unmatched.

Dr. Sobel, with his steely gaze and intrusive questions, provides the game an overt and pointed menace, but even when there isn’t a character staring through the screen, demanding answers about what makes you tick, an invisible force is watching.

I was ten years old. It was a school day, but my morning had begun with a high temperature and breakfast that, uh, didn’t care for the accommodations my stomach provided, so I collapsed on the couch with a stack of old video tapes. Whatever sickness was bringing me down didn’t last long. By afternoon, I was not only back on my feet, but bouncing with the kind of excitement that comes from getting to dig into your Lego bin while the rest of your sucker friends are stuck in a classroom.

“Hey, Mom, look at this cool car I made! Hey, Mom, can I listen to my ‘Weird Al’ CD? Hey, Mom, what religion am I? I know I’m half Jewish, but what’s the other half? Is it Christian?”

The Jewish part was easy to remember because teachers would always ask for my help in December when they tried to explain what a dreidel is, and I’d correct them when they mispronounced “latke.” My mom had been raised Catholic, and we’d get baskets full of jellybeans in the spring and presents under the tree in winter, but those were traditions celebrated by everyone I knew. In my mind, Catholics were indistinguishable from Baptists, Methodists, and Mormons. The details were easy to forget.

I didn’t ask the question seeking a conversation. I wanted a one-word answer. It seemed like a good piece of personal trivia. My mom surprised me, though. She said, “You’re whatever religion you want to be.” I didn’t follow, so she put it in terms that better matched my sensibility.

“You can change your religion like you change your underwear.”

The bulk of Shattered Memories takes place far from Dr. Sobel’s couch. Players assume direct control over Harry Mason, a nondescript guy on the search for his daughter after a late-night car crash. Though he starts the game as the sort of bland cipher that’s so prevalent in video games, it doesn’t take long to start seeing a personality develop; a personality that clearly reflects the results of the personality tests, but that’s only one of the factors at play.

He’s a fairly typical video game man, that Harry Mason. He walks and aims and solves lock-and-key puzzles. What’s unusual is the world he inhabits. No one has a gun except the police officer, and while she might draw it in a few extreme cases, she’s not the type to pull the trigger there’s any way to avoid it. There are monsters, but there’s no combat. There’s a destination, but all roads lead there eventually. This is not a game about problem solving or quick reflexes. The game wants you to succeed, and it puts few barriers in your way. It isn’t a question of if you’ll progress, but how you’ll progress.

Harry needs to get through the woods. What do you do? Do you follow the path that’s been worn through the dirt and the snow? Do you keep your flashlight trained on the ground or do you look up at the trees? Do you wander off to investigate that dark shape in the distance? Do you reference your smartphone’s GPS map? Do you stop to carefully plan a route? Do you walk? Do you run? Do you save your progress and come back later?

Dr. Sobel’s personality tests can be challenging, but at least the parameters are clearly defined. There are questions and there are discrete answers. The rest of the game isn’t framed this way, yet it’s every bit as inquisitive, intrusive, and discomforting. From the time you create a save until the moment the credits roll, the game is watching you.

My cousin Mark is a PhD and professor of philosophy. His wife, Susanna, has a master’s degree in theology and Christian ministry. They are, without a doubt, the most devoutly, conservatively Catholic people I have ever encountered.

Susanna blogs, both personally and professionally. In a recent post, she wrote about peanut butter fudge, of all things. If she keeps peanut butter fudge in her house, she writes, the fudge tempts her. She overindulges, even though she knows gluttony is a sin. She goes on to explain that eating too much fudge does not just affect her body, but her relationship with God, and, in turn, the relationship of all of humanity with the divine. Every sin counts. When she sees evil or moral decay in the world, she takes the blame. She believes that every one of her thoughts and actions that oppose the will of God corrupt the world further. It’s more than a belief. She knows it.

Shattered Memories isn’t a game of big actions.

More than anything, it’s a game of looking. You’ll look at billboards. You’ll look at beer bottles. You’ll look at high school classrooms. If you play this game, you’re going to look at a lot of stuff.

What you’ll seldom see are bright environments, making your flashlight invaluable. Visibility is limited to the specific spot you choose to illuminate. On Wii, the game’s lead platform, the flashlight is aimed with the Wii Remote, drawing a direct line between the player’s wrist and the TV. It’s disarming. Nudging a control stick to adjust your point of view in a first-person shooter, natural as it may feel to longtime game players, is an abstracted motion. Pointing where you’re looking is intuitive in a way that may betray a person’s conscious intention. If you feel yourself being drawn to the pin-up on the wall, the game will notice. A few minutes later, when you meet the buxom cop with a shirt that’s too tight to button toward the top, you’ll know the game noticed.

George Carlin had a bit about smoking pot on an airplane. He said he’d go to the front lavatory to light up in the days before planes had smoke detectors. He picked the front specifically because he’d pretend the mirrors were actually two-way. He’d imagine the pilot watching him from the other side, and he’d offer a puff of his joint. It’s not Carlin’s sharpest work, but it is an image that’s stuck with me. At a glance, what is the difference between a one-way mirror and a two-way? I like to think about who’s on the other side.

I read a picture book while visiting family one summer. I don’t remember what it was called. I don’t remember anything about it except for a page that said you should always say “excuse me” when you burp or fart, even if you don’t think anyone is listening, because God is always listening. I don’t think the book was implying that belching without remorse is a sin. I think it was just encouraging polite manners.

I always say “excuse me.” Even when I’m alone.

Here’s the thing about the flashlight: You can turn it off. You can leave it on. You can aim it where you want to look. You can point the Wii Remote away from the screen. And no matter what you do, you’re doing something. If you’ve turned on the game, then you’re engaged. You’re making choices. You are providing input – even if that input is a lack of input – and the game is reading that.

Physician and essayist Lewis Thomas wrote that a popular doctor is someone who offers answers and actions, but this is not the same as a good doctor. Until relatively recently, medicine was guesswork, alchemy, and superstition. Tuberculosis was thought to be caused by the night wind in the days before bacteria were discovered, and doctors uselessly recommended preventing it by sleeping with the windows closed and treating it with sunlight. Bloodletting was a common cure for a wide range of simple maladies, despite frequently being more harmful than the disease itself. Even with the incredible advances of modern medicine, we frequently fall back on homeopathy and wishful thinking to mask our ignorance. Search online for “health tips” and marvel at the variety of dietary, lifestyle, and attitude changes that promise to reduce the risk of pain and disease without any evidence cited to back up the claims.

This is all to say that we, as humans, have a long history of accepting answers over uncertainty. We want control. If we are ill, we want to fight back, and we want to know what we did to get sick in the first place. Something like the flu is likely to run its course without conscious human intervention, but early doctors were so eager to take action that no one understood the nature of influenza viruses until relatively recently. Centuries of evidence prove that, on the whole, we would let a man cut us with something sharp and unsterile, let him exsanguinate us to the brink of death, or maybe further, before we would admit the limits of our collective knowledge.

Maybe this is why video games are so popular. They’re contained spaces run by logical rule sets. Even when the rules are unclear, we know somebody wrote them. They’re safe little pockets of order.

After the story of Shattered Memories reaches its end, we see, for the first time, the results of the psychological profile spelled out in clear English. That red screen, shown before I’d even pressed a button, warned me that I would be observed, and I played with that knowledge always at the forefront of my mind. I tried to answer truthfully. I didn’t try to skew results with the way I played, but I knew I was playing for an audience. I wanted to know what the game really thought of me.

The final results screen surprised me. “That’s true,” I thought. This game was telling me things about myself I hadn’t noticed.

It’s all a trick, of course. It’s Myers-Briggs. It’s a psychic’s cold reading. The feeling of being watched in every action and non-action, though; the performance of my true self for an audience of whoever – or whatever might be watching – that was real. That was a feeling I’d never felt.

I hadn’t been hurt. I wasn’t worried about being alone. I was having fun with my friend in the plastic tubes at a pizza place. If he needed to walk away, I would still be every bit as content as I was with him at my side.

“I’m leaving you alone, but you’re not really alone because God is here with you.” It wasn’t comforting or discomforting. It was just something Bobby said. It was a thought that he needed.

I still have that memory more than two decades later. That was the first time I was aware that I would never believe in any god or gods the way so many people in my life do. I’m not an atheist. I also don’t know – confidently, assuredly know – that there’s more to the universe than what I see. I know that I change the world around me. I can see the direct cause and effect, but is there more I don’t know about? I don’t know if I’m being watched. I don’t know if it matters. I don’t know.

I don’t know.