Invisible Tactics

Italo Calvino’s novel Invisible Cities tells the fictional story of Marco Polo meeting Kublai Khan. The Khan asks Polo to tell him of the cities within his empire that Polo has visited. However, neither Polo nor the Khan speak the same language. Polo is forced to communicate his descriptions of the cities through pantomime and holding up various objects. From these actions and symbols, the Khan is able to picture the cities Polo has visited. The reader of this novel is never explicitly told if the cities described are how Polo is attempting to describe them, or if they are how the Khan is picturing them after trying to translate Polo’s actions. Either interpretation is valid, and the novel intentionally creates a space for the reader to play with either possibility, and with the potential agendas or meaning within them. It is a novel about translation and perception, and reading it served as the catalyst for me to revisit and rethink Final Fantasy Tactics, one of the games that defined my own relationship with the medium.

Of all the games I own, Final Fantasy Tactics is probably the one I have played more times than any other. I’ve mastered every job, fought on every map, used every broken skill combination and found every secret. In terms of the story, I naively thought I had mastered that too. While filled with political intrigue and wonderful moments, I couldn’t think of the story as holding any more surprises for me. I was sure that I had fully understood its tale of uncovering the truth at any cost and of good intentions corrupted.It wasn’t until I began thinking of the framework of Final Fantasy Tactics that I considered how wrong I had been. The game is not merely a single main character’s story, but the story of many potential narrators, each in some way translating and interpreting each other.

By engaging the story this way, I am not merely a player, but am invited to become one of those potential narrators as well.

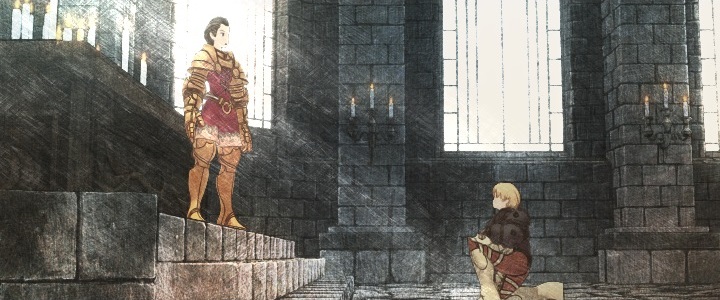

Like Invisible Cities, the narrative framework of Final Fantasy Tactics is based on themes of translation. Final Fantasy Tactics tells the story of the country of Ivalice, a country torn by civil war 400 years ago. The country was saved from destruction by the hero Delita, backed by the common people and the church, who would then become king and the founder of modern Ivalice. The game begins with the discovery of a text, known as the Durai Papers, which contradicts the country’s official history. There are at least three potential narrators of the game. The nature of the story being presented to the player through multiple different potential narrators and translators allows the player a literary game-space in addition to the digital one. This second game-space is where the player can experiment and play with the narrative of the game, just as they play with in the space within the screen.

Tactics Ogre, the spiritual prequel to Final Fantasy Tactics, asks the player to make several challenging moral choices. These choices have direct consequences on the events of the game, and the story changes from the direct actions of the player. Final Fantasy Tactics does not ask the player to make any difficult choices within the digital space of the game. Instead, the main character makes his own choices and we merely act and respond to them within the game. However, I would argue that the game has been asking us to make difficult decisions all along, just in this second game-space. No matter our choices, Tactics Ogre will always end the same way and we will see our choices justified. Final Fantasy Tactics asks us to make choices that cannot be justified within the game itself, but only through experimentation and play within ourselves.

The story of Final Fantasy Tactics never changes within the digital space, but we the players are empowered to change the tone and meaning of the story ourselves. This is a powerful responsibility given to the player.

All games potentially have a secondary game-space for the player to play with the themes and narrative. In general though, we are not taught to think of narrative in this way, and we do not realize the power we have not simply as a passive audience, but as an audience of potential actors and creators. A narrative framework like Invisible Cities or Final Fantasy Tactics attempts to create a situation where the player is confronted with that power. Once aware of this space and their performance within it, a player cannot refuse to take part. The truth about Final Fantasy Tactics is that all along the shifting narrator has been us. We the players are the ones who complete the narrative by deciding who to believe within that second game-space. This empowerment is not limited to one game or book. Any of us can take the empowerment and awareness created in us by Final Fantasy Tactics and bring it to any other game, continuing to change and challenge the narratives we are given.

The main character of the game, Ramza, is barely remembered by the modern , and when he is it’s usually as a heretic or other sinister figure. The story we are told recasts this figure as the true savior of Ivalice and as an heroic activist for peace. The “official” hero Delita is recast as an idealist who turns to activism by the death of his sister Tietra at the hands of the aristocracy, only to become a cynical conspirator, little better than the tyrants he seeks to overthrow. As I am not a citizen of Ivalice, I can only accept that this at face value, and therefore it is easy for me to accept this account as true. In fact, through over a decade of playing this game, I don’t think I ever doubted the Durai Papers represented the true story of Ramza and Delita. Accepting this does not hamper the story or my experience in any way. In fact, accepting the story as given to us leaves us with a very effective and powerful story about a young man learning to accept his privilege and complicity and in turn fight to make the world a better place. It is a story of historical justice and of fighting against oppressive orthodoxy. Ramza’s story is compelling even before anyone challenges it. What is amazing to me is how challenging this interpretation is not only possible, but that the game is even open to these challenges.

The main character of the game, Ramza, is barely remembered by the modern , and when he is it’s usually as a heretic or other sinister figure. The story we are told recasts this figure as the true savior of Ivalice and as an heroic activist for peace. The “official” hero Delita is recast as an idealist who turns to activism by the death of his sister Tietra at the hands of the aristocracy, only to become a cynical conspirator, little better than the tyrants he seeks to overthrow. As I am not a citizen of Ivalice, I can only accept that this at face value, and therefore it is easy for me to accept this account as true. In fact, through over a decade of playing this game, I don’t think I ever doubted the Durai Papers represented the true story of Ramza and Delita. Accepting this does not hamper the story or my experience in any way. In fact, accepting the story as given to us leaves us with a very effective and powerful story about a young man learning to accept his privilege and complicity and in turn fight to make the world a better place. It is a story of historical justice and of fighting against oppressive orthodoxy. Ramza’s story is compelling even before anyone challenges it. What is amazing to me is how challenging this interpretation is not only possible, but that the game is even open to these challenges.

The story we are told is largely from Ramza’s point of view. If we think of the game as being Ramza’s account, then we have to ask how reliable Ramza is as a potential narrator. He is despised by the government and most of the country, constantly on the run and afraid for his life. His account conveniently both redeems himself and exposes his enemies as frauds or liars. It also allows him and his allies to slip away from history, leading the reader to assume they died or disappeared in their final battle. If the story is merely Ramza attempting to escape his enemies and strike back at them at the same time, it is remarkably effective at doing so.

Even if the account is true, there are questions I want to ask Ramza. How much of his account of Delita is based on anger or guilt? Is he attempting to make amends with his one-time friend? Ramza absolves himself of Tietra’s death, but then seems to forget her existence after doing so. He does not bring her death up when dealing with his brothers, nor does he tell his sister and Tietra’s best friend that it was their brother that was directly responsible for her murder. Tietra’s death is reduced to motivation for Delita’s schemes, but is also reduced even further to excuse Ramza for the deeds of other nobles. Can we really trust Ramza’s account of Delita if he is unable to truly deal with his complicity in the deaths of Tietra and countless other oppressed commoners?

About midway through the game, we are introduced to Durai Olan, the man who will go on to write the account we are playing through. Durai is the son of “Thunder God” Cid, a kind and valiant aristocrat like Ramza, and he quickly grows close to our displaced yet noble Ramza. Durai ends up writing his account in order to disclose the truth about Delita’s rise to power and Ramza’s role in saving the country. Its certainly possible that Durai merely wanted to preserve his friend’s reputation or fight for lofty ideals of truth and justice no matter the cost. It would certainly be within the character of the Durai we meet within the game. But then, the Durai we meet is potentially the creation of the real Durai, who would certainly cast himself as the noble, truth-seeking martyr to win us to his side.

What if Durai’s true purpose is more sinister?

According to the game, modern records of Ramza are rare and fractured. Its possible that the real Durai never even met Ramza, or even if he did is only using his “friend” as a tool to push his agenda. What agenda would that be? Throughout the game, we see that Ivalice is led to ruin by the machinations of corrupt aristocrats and politicians, but we are also shown over and over again that the uprisings and machinations of the underclass are just as harmful or dangerous. Even noble peasant heroes and activists such as Delita and Wiegraf are shown to eventually be corrupted either by desire for revenge or actual, literal demons. The only characters we can trust are those nobles who are kind and wise enough to represent all people. Durai’s account can be seen as aristocrat apologia, making the case that Ivalice would’ve been better off if only everyone had listened to or followed the “good” nobles like Ramza or Cid (or Durai).This potential reading offers a Durai who argues against popular revolt and political revolution in favor trusting in select gifted individuals. Is Durai attempting to redeem his father’s name through Ramza and perhaps position himself politically against Delita? Is his story of demons and corruption meant to show us that the common man still needs the wise, steady hand of a “true” noble?

Of course, the account may be written by Durai, but we are only getting it through the translation of another character. At the start of the game we are introduced to Alazlam, an Ivalician scholar who is presenting his findings on the heretical Durai Papers. During the introductions to each chapter, we are shown a few sentences of Alazlam’s notes on the time period, occasionally displayed through an agonizingly slow text crawl, which I always interpreted as representing Alazlam having difficulty translating or reading a particular passage in the papers. However, aside from these few moments Alazlam is never overtly a traditional narrator. There’s no indication that the story we are being presented with is as Alazlam would narrate it. Aside from his intro and outro, the only reminder we have that Alazlam is our link to this narrative is through his appearance in the chronicle, the record of every event and character the player encounters.

The only role Alazlam plays for certain is to remind us that this is a historical account from a text, not necessarily from reality. But what if the story is being told to us from his perspective? What biases or agendas might he be bringing?

The most obvious agenda is given to us directly at the end of the game. Alazlam is a descendant of Durai, and Durai was martyred by the church for writing this text. Is Alazlam concerned with the truth, or with redeeming his family name? Alazlam writes from an Ivalice 400 years after the events of the game. An Ivalice created from the events of the civil war whose history he is both rewriting, and our only source for. Even if the actual story matches the official record, it is certainly possible that the church did indeed become corrupt and oppressive by Alazlam’s time. If Alazlam comes from a world run by an oppressive theocracy built on the ashes of the war, he might be inclined to present the story in a way that challenges the myths of that regime. Alazlam’s agenda might not even be political, he could have simply used the most scandalous account possible to build a career on. A story where the fondly remembered king turns out to be a murderous conspirator and a heretic proves the corruption of the dominate religion could mean tons of book deals and universities offering him all the tenure and grad students he could want.

The most obvious agenda is given to us directly at the end of the game. Alazlam is a descendant of Durai, and Durai was martyred by the church for writing this text. Is Alazlam concerned with the truth, or with redeeming his family name? Alazlam writes from an Ivalice 400 years after the events of the game. An Ivalice created from the events of the civil war whose history he is both rewriting, and our only source for. Even if the actual story matches the official record, it is certainly possible that the church did indeed become corrupt and oppressive by Alazlam’s time. If Alazlam comes from a world run by an oppressive theocracy built on the ashes of the war, he might be inclined to present the story in a way that challenges the myths of that regime. Alazlam’s agenda might not even be political, he could have simply used the most scandalous account possible to build a career on. A story where the fondly remembered king turns out to be a murderous conspirator and a heretic proves the corruption of the dominate religion could mean tons of book deals and universities offering him all the tenure and grad students he could want.

So then: Whose Ramza am I playing as? Am I playing the objective Ramza going through the actual events? Am I playing the Ramza he would present himself to Durai as? Am I playing as Durai’s Ramza, created for his text and designed either to redeem Ramza’s legacy or to further a political agenda? Am I playing as Alazlam’s Ramza, created from the historian’s perception of the texts he is translating and shaped by his modern biases, family history, and agenda? Or am I playing as myself, and the Ramza created is from my own perceptions of the story Alazlam is telling me? No single possibility is more valid than the other, and this space created within my perception of the game allows me to experiment with all the options. A new space created by my interaction with the game, existing at the same time as the digital space where I juggle numbers and move characters around a map.

As I begin Final Fantasy Tactics for what feels like the hundredth time, I begin deleting the extra generic characters I don’t have any use for. One of them responds to my attempt at dismissal with “What!? Why do you think I came along with you!?” I stare at the soldier, transformed from a generic, identity-free sprite into a character with their own ideas and goals. The game will never tell me why Lefwyne the chemist came along with Ramza, or why he expects Ramza to remember and be swayed by this purpose. Instead the game is asking me to provide this, to perform as well as play. For the first time I pause before selecting “yes” to dismiss a generic soldier and find myself asking whose story would be affected by this action, as well as what story I want to tell.

2 Comments

Alazlam’s part in this reminds me of how Tolkien claimed to treat the Middle Earth stories as documents he found, and was translating for wider release. When he rewrote the Gollum section of the Hobbit to work in the changes to the character in the Lord of the Rings. If I recall correctly, he explained it in one of his letters to a fan as uncovering a different version of the same story among all the “documents” of Middle Earth that Sam had left. Looking at the whole Middle Earth edifice in that way, especially the Silmarillion, gives a similar kind of reader agency to the process.

And of course Tolkien was riffing off of James Macpherson and his Ossian Cycle in the 18th century, which were successfully passed of as authentic ancient Celtic works for a very long time, and had a tremendous influence on European intellectual life at the time. Who does Goethe become without Ossian to inspire him? What does authenticity even represent? No one reads Macpherson today because his work is “fake”–but what does fake even mean in regards to fiction? There’s something to unearth in regards to digital media along these lines, and I think this article could benefit from a widening of the scope beyond the narrative machinations of a single game.