Biographical Discourse

History is the act of keeping our stories alive: what has come once can come again. It is a theme with which Christine Love’s Analogue: A Hate Story plays. No matter how progressive one’s society may seem, history is full of lessons of cycles which repeat themselves: backlashes against the liberalism of before, or an absolute loathing of conservative measures taken in the past. History is therefore a story which has survived, and how the story is heard is influenced heavily by the storyteller.

The exploration of the Mugunghwa, a colony ship whose sudden silence remains a mystery, in Analogue is an exploration of primary documents which serve as the most basic version of a storyteller for the player. A primary document is one that directly chronicles a portion of history directly from someone recording their own voice during that period; it is presented as is, with all of its biases, and a more narrow view of all that is happening. Analogue presents a game full of such primary documents. The player is not just someone theoretically sifting through these logs found on the Mugunghwa to figure out what has happened; the player is directly implicated in terms of the future of what shall happen, including how the events that did happen are perceived.

Unlike reading just a primary document, in Analogue there are added filters including one in which the player adopts a persona. This persona can be as close an approximation as the person playing it wants it to be: whether it is themselves or a constructed personality. The actions of the role to be played? Digging through digital archives to figure out what happened on the Mugunghwa and discover why it has become a derelict piece of floating space debris. Instead of having everything readily available, there is a bit of digital sleuthing involved, mostly a function of gatekeeping that is explained as working with the AI to unlock more of the archives.

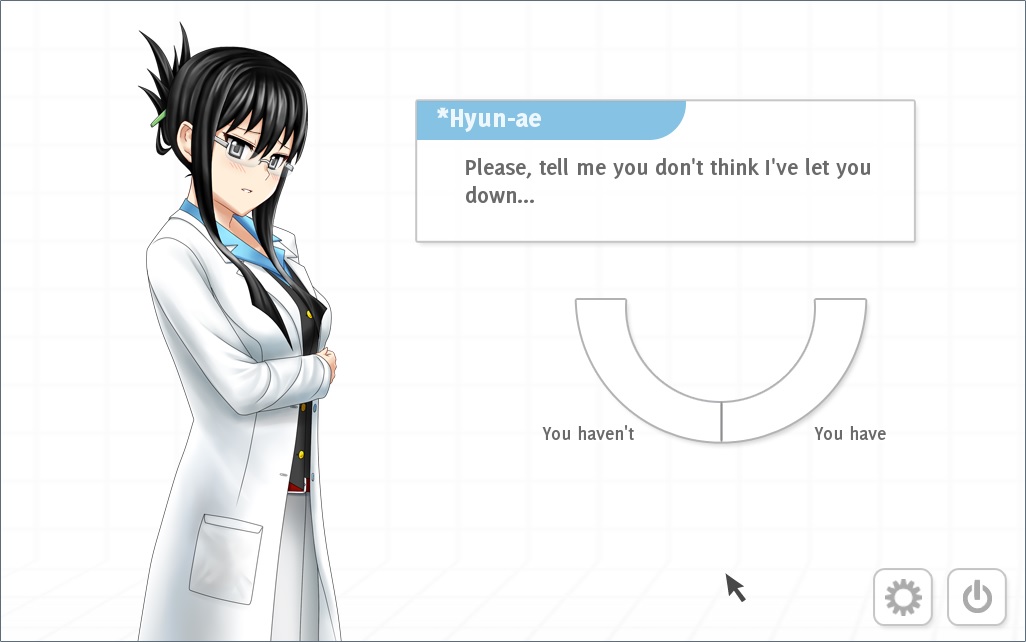

The player works through the story reading various log entries from residents of the ship. Each of these entries can be shown to the AI present, who will give their own commentary and viewpoints. There are times when the exact same log entry can be shown to either *Hyun-Ae or *Mute (the AI entities of the game) and wholly different remarks are given to the player, each having a different story to tell, or spin on what exactly happened, despite what was written. This turns both AI into historians, who are trying to filter the stories read with their own context and their own commentary.

Which brings into question the motives of the person giving this information, and why they are doing so. At first *Hyun-Ae clearly wishes to paint herself in a positive light, as does *Mute. They both present stories they think would bring you to their side, as they both have their viewpoints they wish you to share. Instead of just passively reading documents, in particular diaries, there is the added consideration that the game is guiding the player to interact with people who lived that history and are providing context for what occurred.

Choosing the order in which the documents are read makes a subtle decision in how exactly the story is unveiled. Each AI also has certain pieces of the story they wish to present, or call you to make a judgment on: do you find willful disobedience in the face of a culture that is not your own deplorable or commendable? Can a woman be forgiven infidelity in a society where she has no voice? While there are value judgments I could make regarding which AI represents what viewpoint, this is an experience the game clearly gives you: each player is going to have their own reactions based on how they experienced the story, and with which historian’s side of history they more prefer. The order in which we find out information can very much color our later opinions as things progress.

Analogue does offer a choice: which companion ultimately is the one with whom you side? Which offers the version of history that speaks closest to you? These are judgments we are likely to make anyway, but in Love’s Analogue, she guides that course of thought. History will survive, but which version of it will be perpetuated? Which judgments?

While a diary would allow skipping around, there is a very clear intent of how it is to be read. With Analogue, the player is given the illusion of being able to choose which stories they’ll read at various points. Things are fragmented so the stories the game tells are slowly constructed in a manner of the developer’s choosing, but that the player can later go back and read in their own order. It is even possible to completely miss bits of the log files, and thereby not completing the ‘whole story,’ but still experiencing a very functional one.

The two AIs in Analogue, are in many regards opposite sides of the same coin, and they each have a clear goal in presenting this information. What this reminds us to do is to do what we theoretically should already be doing with any history we read: parsing what exactly is being said, what limits the narrator’s point of view, and how does it connect to the world around them? The AIs are not merely custodians who mete out story, but have distinct personalities. They are further a lesson that any bit of text that survives through history is actually full of some manner of personality, whether it be lively and spirited or dry and judgmental.

While they may only be NPC AI companions, *Hyun-Ae and *Mute are a reminder that texts are something with which we interact, and each person will bring something different to that text. Who gets to tell the story is the ultimate winner in the game of history, as per our usual clichés, but perhaps history is merely a pretty AI who wants to make us happy so we hear what we want, and can delete the rest.

1 Comment

I often find myself getting in semantic debates (usually on Twitter—the BEST place to have semantic debates!) about the term interactivity. I can’t stand it when people try to separate videogames from The Rest Of All Art Ever because they are ‘interactive’ while all other texts/works are not interactive. I’m more of the opinion that every text ever is interactive! Every kind of text has a material element that needs to be engaged with, whether it is an Xbox controller, a book page, an art gallery wall, whatever. You need to do something with your body in relation to the material artifact in order to consume and interpret it.

I think it is Espen Aarseth who talks about hypertext literature (these days I guess he’d be talking about Twine). He notes how people often hold up hypertext and digital texts generally (including videogames) as offering more ‘choices’ and freedom than books. But, really, you have LESS freedom. In a hypertext story or a Twine game, I can ONLY go where the designer has placed links. In a book, I can turn to any page whenever I want, start reading from any word. The author isn’t here to stop me.

So I think with games like Analogue, that notion that an engagement with any kind of text is active and interactive shines through, and it calls us to reconsider how we think about videogames. Not as some brand new thing totally different and special and detached from the rest of the world’s creative works, but just another kind of interaction between audience and text. Or something.