God Bless You

There’s the story of the time I left the restaurant after catching a late dinner, and he looked at me. We were waiting for the pedestrian light at a busy street corner, and I thought nothing of it because he could easily have been looking at someone—maybe a trailing friend—behind me. And so I just kept walking and he kept looking back, and it didn’t take long for me to figure that he was looking back directly at me. Ogling, you might say, wide-eyed. And soon he started trying to keep pace with me and I started glaring back, until eventually he crossed the street.

Okay, that’s over. He gets the hint.

Oh, wait a minute.

He starts waving and calling me over. He looks like he’s about to turn onto another street but instead he keeps following me, keeping pace, calling me. I shoot him the finger but I don’t think he gets it. It’s crowded, sure, but it’s still dark out and my bag is heavy and my knees are killing me, and I just want to get home in peace. So I gather the bit of energy I have and I bolt and I don’t stop until I’ve lost him, and I’m checking over my shoulder for the rest of my walk.

Sometimes they cat-call, but a lot of the time they might just stare. If they’re really bold they might follow you around for a block or two. And even more generally, it’s only the idea of the threat itself that keeps you guarded, wondering if he’s looking at you, or past you. Sure, he sounded polite. You want to believe the barista at the corner café was only engaging in polite banter, but if you’re too friendly he might take that as an opening to ask you what you’re doing tonight, and if you’d like to watch a movie at his place.

Excuse me, but I didn’t come here to hook up; I came here to read my book in peace, thank you.

You don’t even say this because, who knows? You’re so certain he’s up to something, but you can’t prove it. And if you talk back, you just look like the ice queen.

You can never be sure of people’s intentions.

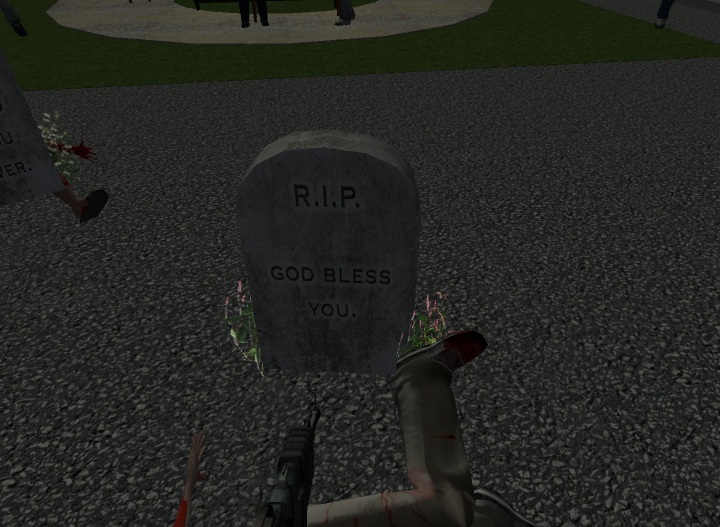

I guess I was hoping for some kind of catharsis from Hey Baby, available as a free, in-browser first-person shooter. Here, I’m a woman walking through town; I have no idea what I look like, but I have an assault rifle. I can use it liberally on men who approach me with propositions or verbal abuse, and I do. When they die, they leave a tombstone etched with what they said to me, from the seemingly innocuous to the unequivocally degrading and obscene. That is how they will forever be defined for me, mortally and eternally. That is the memory they leave for me. Sometimes I don’t even wait until they say anything.

They seem to come out of nowhere, and there seems to be far more of them than there are other women or people who just keep to themselves. We can decry this as unrealistic: surely, my actual experience out in public hasn’t been this urgently dangerous every single day. And surely, even if I did go after all of my harassers with a loaded weapon (and yes, I have thought about it) I would probably be writing this article from the inside of a jail cell. But Hey Baby gets something right—no, I’m not necessarily harassed or followed each and every second I leave my house, but the threat hangs over me like a fucking thundercloud.

For every one of them that says “Hello,” or “Nice weather we’re having,” or “God bless you,” and for every one that waves or nods or smiles sweetly, there is a part of me that wants to feel flattered and pleased to make an amicable connection with another person. But I struggle with these feelings—what I believe are universal and innocent feelings—of desiring validation. I struggle because for every polite comment there’s the looming suspicion that it’s all some kind of trap—that it’s a trap and they’ve been set everywhere. Unlike Hey Baby, men with passing comments (let me refrain from calling them all “harassers”) aren’t all upfront about what they mean. But it just takes a few instances of bona fide stalking and verbal abuse to stick in your mind, to make you unsure. Something about his tone or—did he look at me in a funny way?

Look, there was the time when he followed me from his car. There was the time when he waited, parallel-parked between other cars and idling at the curb, and then he drove up the street to try to throw me. And there was the moment of déjà vu when I saw him idling again, the same way but further down the street, a few minutes later. And then when he stopped on the bicycle path where he knew I’d be defenseless, and I crossed the street assuming he wouldn’t pull an obvious u-turn. And when he finally drove away I bolted to my house and locked the door. I cried and hyperventilated while poking my head through the blinds stealthily to make sure he wasn’t still circling around.

And there was the other time he found me walking home—the same guy, but in a different place. And this time he picked up a friend and trawled the streets to find me and try to usher me over to the car. I gave them both the finger—because, you know, I don’t have an assault rifle—and they seemed genuinely offended when they finally drove away. What a cold bitch I must be.

I remember the red sedan with the rusted carriage and I remember being too scared and panicked to catch the license plate number, and I remember his eyes looking at me like I was a rare bird or something.

I remember him vividly just like I remember the guy in the silver Subaru, but that happened in broad daylight. I could feel him looking at me from his dash and I could feel him trailing me slowly up the street to my boyfriend’s house. I remember the way he bore his eyes into me while I walked across the lawn to avoid him. That time I was implored to call the cops. They came and asked if I had gotten the license plate number.

Heh.

I don’t have to know what my avatar looks like, because it doesn’t matter. They come at you in Hey Baby like an endless wave of zombies drawn to a pound of flesh. When they die they let out a cry like some kind of monster. There’s this looping ice cream truck music and I feel like an escaped circus animal. Yes, I’m the one that feels like the animal.

I walk into one part of town and they swarm me and I shoot around me until I’m encircled by gravestones, and I actually do feel confined. The only way to get out is to keep moving, to jump out, because fighting back just seems to place more obstacles in my path.

Even though they don’t physically hurt me, I feel my autonomy and well-being threatened because there’s only one of me and an endless supply of them. I don’t know whether the “nice” ones have the same intent as the rude ones. It’s suffocating. I want to make it stop but it doesn’t and I can only take 20 minutes of this. It doesn’t make me feel empowered, or sexy, or in control. It’s all just a reminder. I’m a trapped animal. Am I even talking about the game anymore?

Now, say I am talking about the game. Normally I’d provide my analysis backed up with all sorts of links and citations and quotes to support my arguments. But here I feel like the substance of my own experience in everyday life ought to be enough to underpin my feelings about Hey Baby. I mean, it ought to be, but it’s not.

What usually happens when I present my experience is something to the tune of scorn over my obvious vanity. How hot I must think I am if I think I’m getting so much attention. How I must be lying or overstating things. How I should be grateful. How much of a narcissist I must be.

And how can I be so cold to men who are just being nice, just complimenting me? And how can I expect men not to ogle me or proposition me when I dare to expose any skin or put on makeup? And how can I mistrust men or judge men and this is why men are intimidated around women. Because we’re such cold and unapproachable cockteases.

I mistrust men because I’m stuck-up and irrational. My experiences are imagined or overstated. I’m doing this for attention and sympathy, because you know, I’m so vain.

The unequivocal truth of fatal bullet wounds does not spring anybody to attention in Hey Baby. They deter no one. They clue no one into my character’s feelings. They don’t signal to anyone—harasser or not—that there’s a problem. I am a silent protagonist. I am an invisible protagonist. There are lots of people here to hear me fall but I don’t make a sound.

So I can’t just rely on the authority of my own experiences. Kieron Gillen incisively articulated exactly my feelings back in 2010:

“The game’s rubbish, of course. But the one thing it does well is show how what you may think is an innocuous compliment feels in the context of a woman’s life. You approaching a woman in the street and being what you think is politely flirty is a different thing when, down the street, someone’s suggested that maybe you’d like to suck my dick and you’re a fucking bitch if you don’t.”

From her perspective, it’s a culture of harassment she has to either politely deal with or ignore.

From your perspective, you’re just showing how you feel.”

He’s right: the game, from a technical standpoint, isn’t fabulous. It’s buggy and unpolished and—again, he’s right—it rings conceptually with all the same levels of sophistication and intellect as Postal, with all the same polish as a dead enemy that won’t despawn. A “premium” version of the game is available for purchase, for which the site offers,

- Cool advanced technology allows you to get up close.

- Unique over-the-top gameplay.

- High body count.

- Crazy action! More enemies! More blood!

All of the above could be read as tongue-in-cheek or as perfectly earnest; I don’t know. But the only reason I care about the technical aspects of the game at all is because I don’t know if the design of the game is subversively screaming with all the feelings of entrapment that it evokes in me, or if it’s just screaming. But Hey Baby, with or without sophistication, symbolizes the realization of a perpetual, pervasive exasperation. What I wear; where I go; how I act; if I dare to flirt; if I walk down that alley; if I fight back I’m an uptight bitch; if I don’t then it’s my fault for standing up for myself; and they just keep coming; and they just keep coming; and I don’t know who to trust; and I don’t know what he expects; then I’ve asked for it; then I’m exaggerating; then I’m lying; then maybe I should just hide myself away because that way they won’t see me.

I can say without looking at the stats that this happens or has happened to just about every single woman you know, at some point. I’ve shared the stories. More women are coming forward. Electronic artist Claire Boucher, spoke about her experiences with sexism and harassment recently, posting on Tumblr:

“I don’t want to be molested at shows or on the street by people who perceive me as an object that exists for their personal satisfaction. I don’t want to live in a world where I’m gonna have to start employing body guards because this kind of behavior is so commonplace and accepted and I’m pissed that when I express concern over my own safety it’s often ignored until people see firsthand what happens and then they apologize for not taking me seriously after the fact…”

Boucher shouldn’t need bodyguards.

The woman in Hey Baby shouldn’t need a gun.

I shouldn’t need Gillen’s help for this.

The men on the street. The men in their cars. The men on the internet. The men on OKCupid. The men who think an occasion to look is an invitation to proposition, holler at, stalk, touch. The ones that kettled me, trapping me while I was on the metro, one sitting next to me and one standing in front of me—and they also seemed genuinely offended that I wouldn’t follow them to the bus stop. They’re the men who make me palpitate in a fit of anxiety when another man looks at me the wrong way the next time I’m riding the metro. They make it hard to know what “God bless you” actually means.

I don’t hate you. I don’t want to fear you. I don’t want to shoot you. But I don’t feel like a survivor, or a winner, or an overcomer, because it doesn’t ever stop. The fear and the threat are always there to control me and to shame me and to turn me into a zoo of body-image complexes and a compromised sense of agency and a corrupted desire for external validation.

People made Hey Baby because this frustration resonates with them, but I don’t believe it’s about catharsis. I think Hey Baby is about futility. I think it’s about intimidation and rage and frustration and the impossibility of relief, of escape.

If you are a man, I don’t believe you are a mindless zombie unable to overcome your own programming. I think you are capable of having your reason and compassion appealed to. I don’t despise you or begrudge you universally but unless you give me a good reason to disarm myself, to disabuse myself of my fear, I will always have my finger on the trigger.

1 Comment

Something really important Lana brings up is how women deal with men who are well intentioned but are in a sea of hostiles, as Hey Baby would put it. I feel like a lot of detractors to the thinking going on here we be shocked to realize people don’t like being victims. There’s never anything good from being a victim, you still have to carry the consequences of what someone did to you once your survive it, even if you were ‘right.’ Being ‘right’ is oddly important to people, which is why some would nit-pick at women to take things at a case-by-case basis instead of damning all men. But Hey Baby was a perfect choice to illustrate that; you gun down even your opportunities because you can’t tell them all apart, and you don’t have the chance to find out.

A large part of this, as Lana points out, is being conflicted with yourself. It’s not fun being skeptical of someone who might actually just be a nice person. But as per my experience, even the nicest seeming person can grab at your body without your permission and completely ruin any fantasy of magical random meetings. Doing what I can to ignore everyone when I’m in transit never makes me feel good, but it’s always better than the alternative.

I felt particularly compelled to say something because just after we launched the site with this piece on it, I went out and actually had a guy cat call me with ‘Hey baby!’ It was surreal, but then again not. I think what’s actually surreal is how much people still seem to be skeptical of street harassment being a problem. And this isn’t even going into how much women are being reminded that they consumable sexual objects often with autonomy, which is a whole other things all together.